SAT Reading Comprehension Requires Active Annotation, Not Speed Reading

Feb 03, 2026

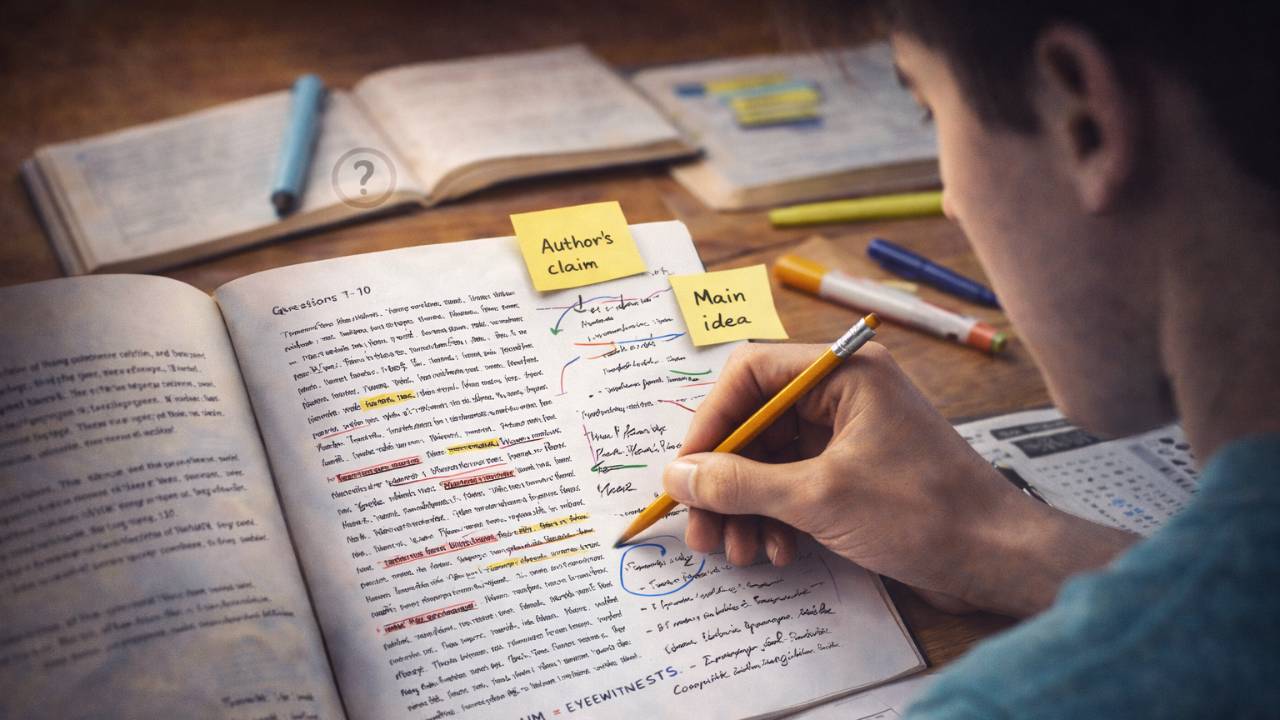

The most damaging misconception in SAT preparation is that reading faster leads to better scores. Walk into any test prep center and you will hear instructors teaching students to skim passages, hunt for keywords, and race through questions. This approach fundamentally misunderstands what the SAT Reading section actually measures. The test does not reward speed. It rewards precision, evidence-based thinking, and the ability to track complex arguments through dense academic text.

Students who systematically annotate for argument structure and evidence relationships consistently outperform those who rely on speed reading techniques. The difference is not marginal. When cognitive lab studies examine how successful test-takers navigate SAT passages, they find a clear pattern: high scorers interact with the text through selective annotation, creating external memory aids that reduce cognitive load and improve accuracy. They do not skim. They engage.

This distinction matters because it reveals a deeper truth about SAT preparation. The skills that produce lasting improvement are the same skills that support college-level academic work. Active annotation is not a test trick. It is a fundamental reading comprehension strategy backed by decades of learning science research. When preparation programs teach annotation as a systematic skill rather than a tactical shortcut, they build capabilities that transfer beyond the test into actual academic performance.

The Cognitive Science Behind Active Annotation

Understanding why annotation works requires examining how the brain processes complex text. Working memory, the cognitive system responsible for holding and manipulating information during reading, has strict capacity limits. Research consistently shows that humans can maintain only about four chunks of information in working memory at once. When students attempt to speed read through dense SAT passages, they exceed these limits, causing critical information to be lost before it can be properly encoded.

Active annotation solves this problem by creating what cognitive scientists call external memory aids. When students write brief marginal notes summarizing paragraph functions, mark where evidence appears, or note shifts in argument, they offload information from working memory to the physical page. This reduces what researchers term extraneous cognitive load, freeing mental resources for the deeper processing required to understand complex arguments and identify subtle relationships between ideas.

Neuroscience is compelling. Brain imaging studies reveal that active annotation engages multiple neural pathways simultaneously. The physical act of writing activates motor regions. The process of summarization engages language processing centers. The visual markers create spatial memory cues. This multimodal engagement produces what learning scientists call dual coding, where information is encoded both verbally and visually, creating stronger and more accessible memory traces.

More importantly, annotation transforms reading from passive reception to active construction. When students annotate, they must continuously make decisions about what matters, how ideas connect, and where arguments shift. This metacognitive monitoring, the process of thinking about thinking, is precisely what distinguishes expert readers from novices. It is also exactly what the SAT Reading section is designed to measure.

Why Speed Reading Fails on the SAT

The speed reading approach fails because it misdiagnoses the challenge. Students do not struggle with SAT Reading because they read too slowly. They struggle because they cannot reliably identify and track the specific evidence the test requires. Every correct answer on the SAT Reading section must be directly supported by the text. The test explicitly punishes inference, assumption, and any answer not anchored to specific textual evidence.

Speed reading, by definition, involves selective attention and aggressive filtering. Readers trained in these techniques learn to skip supporting details, ignore qualifying phrases, and focus only on what seems immediately relevant. This works well for extracting general themes from business books or news articles. It fails catastrophically on the SAT, where the difference between correct and incorrect answers often hinges on precise wording, subtle qualifications, or specific evidence that speed readers routinely skip.

Consider how the SAT constructs wrong answers. Test makers deliberately include choices that seem reasonable based on general understanding but lack specific textual support. They write answers that would be correct if a single qualifying word were different. They create options that accurately describe common interpretations of the topic but do not match what this particular passage actually says. Speed readers, operating on general impressions rather than precise textual evidence, consistently fall for these traps.

The timing argument for speed reading also collapses under scrutiny. The SAT provides approximately 75 seconds per question, including reading time. This is not a speed test. Students who annotate effectively spend more time on initial reading but save substantial time on questions because they can quickly locate relevant evidence using their annotations. They avoid the costly re-reading that plagues students who rushed through the passage without creating any reference system.

Building an Annotation System That Works

Effective annotation for the SAT requires a systematic approach tailored to the specific demands of the test. This is not about highlighting everything or writing extensive marginal notes. Research from cognitive load studies shows that over-annotation can be as problematic as under-annotation, cluttering the page and making it harder to locate key information quickly.

The most successful annotation systems share several characteristics. First, they are minimal and symbolic. Instead of writing complete sentences, students develop personal shorthand: arrows for cause-effect relationships, plus signs for supporting evidence, question marks for claims that need support. This symbolic system reduces the time cost of annotation while maintaining its cognitive benefits.

Second, effective annotation focuses on structure rather than content. Students should mark where arguments begin and end, where evidence appears, where authors make concessions or acknowledge counterarguments. A well-annotated passage reveals the skeleton of the argument at a glance, allowing students to navigate quickly to relevant sections when answering questions.

Third, annotation must be selective and strategic. Not every sentence deserves a mark. Students should annotate moments of transition, claims that seem likely to be tested, and evidence that supports major arguments. The goal is to create a map of the passage, not a translation of it.

Genre-Specific Annotation Strategies

Different passage types on the SAT require adjusted annotation approaches. Science passages demand attention to experimental design and causation. Students should mark hypotheses, methodologies, results, and conclusions. They should note where authors distinguish between correlation and causation, where they acknowledge limitations, and where they suggest future research directions.

Historical and social science passages require tracking multiple perspectives and chronological developments. Effective annotation marks whose viewpoint is being presented, how different perspectives relate to each other, and where the author's own position becomes clear. Students should note dates and sequence markers that establish chronological relationships.

Literary passages present unique challenges because they often test tone, characterization, and implied meaning alongside literal comprehension. Annotation here should track emotional shifts, character motivations, and moments where narrative voice differs from character perspective. Students should mark examples of irony, symbolism, or other literary devices that affect meaning.

Paired passages, which ask students to compare two texts, require annotation that explicitly tracks relationships. Students should mark points of agreement and disagreement, note where authors address similar topics with different approaches, and identify where one author might respond to the other's claims.

The Transfer Value of Annotation Skills

The annotation skills developed through structured SAT preparation transfer directly to college-level academic work. University courses require students to engage with complex texts, synthesize multiple sources, and track sophisticated arguments across lengthy readings. Students who have developed systematic annotation habits through SAT preparation arrive at college with a significant advantage.

Research on college readiness consistently identifies active reading strategies as a key differentiator between students who thrive and those who struggle in higher education. The ability to identify argument structure, track evidence, and maintain external organization systems predicts success across disciplines. These are not test-taking skills. They are fundamental academic competencies.

This transfer value extends beyond reading comprehension. The metacognitive habits developed through annotation practice improve learning across domains. Students who learn to monitor their understanding, identify confusion, and actively engage with challenging material develop what researchers call self-regulated learning skills. These capabilities affect performance in mathematics, science, writing, and virtually every academic domain.

The equity implications are significant. Students from under-resourced schools often arrive at the SAT without exposure to these fundamental strategies. When test preparation focuses on tricks and shortcuts rather than building genuine academic skills, it perpetuates disadvantage. But when programs teach annotation as a transferable academic skill, they provide tools that support long-term academic success regardless of background.

Implementing Annotation Practice in Curriculum

Building annotation skills requires structured practice with increasing complexity. Students cannot simply be told to annotate. They need explicit instruction in what to mark, how to create efficient notation systems, and how to use annotations when answering questions.

Effective curriculum sequences annotation instruction across multiple stages. Initial lessons focus on identifying passage structure: introductions, topic sentences, transitions, conclusions. Students learn to see the architecture of academic writing before attempting to annotate details.

Intermediate practice introduces genre-specific annotation strategies. Students learn how scientific passages differ from historical arguments, how literary analysis differs from social science research. They develop flexible annotation systems that adapt to different text types while maintaining consistent core principles.

Advanced practice integrates annotation with question-answering strategies. Students learn to use their annotations as a reference system, quickly locating relevant evidence without re-reading entire passages. They practice distinguishing between answers that seem reasonable and answers that have specific textual support.

Throughout this progression, students should receive feedback not just on whether they answered questions correctly, but on whether their annotations effectively captured passage structure and evidence. This metacognitive reflection helps students refine their annotation strategies and understand the connection between active reading and comprehension.

Measuring Progress Beyond Speed

Programs that emphasize annotation over speed reading must also shift how they measure progress. Traditional metrics like words-per-minute or time-per-passage miss the point. What matters is accuracy, evidence identification, and the ability to navigate complex arguments.

More meaningful assessments examine whether students can identify the main argument of a passage, locate specific evidence when prompted, and distinguish between supported and unsupported claims. These capabilities, not reading speed, predict SAT performance and college readiness.

Progress in annotation skills often appears as initial slowing followed by dramatic improvement. Students who are learning to annotate systematically may take longer on early practice passages as they develop their notation systems and learn what to mark. But as these skills become automatic, they achieve higher accuracy with less total time investment than speed readers who must constantly re-read to locate evidence.

This pattern reflects the deeper learning process that annotation supports. Unlike surface-level test tricks that must be consciously applied, annotation skills become integrated into students' reading process. They stop being a test strategy and become simply how these students read complex texts.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: active annotation, not speed reading, builds the comprehension skills the SAT Reading section actually measures. This is not about gaming the test. It is about developing fundamental academic capabilities that transfer to college coursework and beyond.

When we teach students to annotate systematically, we teach them to think about how arguments work, how evidence supports claims, and how complex texts convey meaning. These skills matter far more than any test score. They represent the difference between students who can decode academic texts and students who can truly engage with ideas.

The choice between speed reading and annotation is really a choice between short-term test performance and long-term academic development. Programs that prioritize annotation may not promise miraculous score improvements in two weeks. But they build lasting capabilities that support success in college and beyond. In an educational landscape too often dominated by shortcuts and quick fixes, teaching annotation as a fundamental academic skill represents a return to what actually works: structured practice, cognitive engagement, and evidence-based instruction that builds transferable competence.

Explore Evidence-Based SAT Preparation

For educators and families seeking SAT preparation grounded in learning science rather than test tricks, explore the comprehensive curriculum resources at Cosmic Prep. Our materials teach annotation as part of a systematic approach to building academic reading skills, with dedicated guides for SAT Reading, Grammar, and Math that emphasize deep understanding over superficial strategies.